Interpreting Beethoven: Double Beat Theory

I know it seems like this project is all about tempi and metronomes and here comes another article about it, but this is very important when discussing Beethovens music, and I will soon publish articles concerning other topics. But as we have seen in the letters in the previous articles, the Metronome Markings and tempi was one of, if not the most important aspect of Beethovens music according to the composer himself. That is why I have devoted a big part of this project to that subject, and I hope I can bring focus to the Metronome Markings and influence other musicians to give tempo a bigger attention when working on a piece of music, instead of choosing a tempo just because everyone else plays like that. It is okay to disagree with me and believe whatever theory you think is right, but I think it’s quite sad to see how important the metronome markings was for Beethoven, when todays musicians simply ignore it!

DOUBLE BEAT THEORY

So what is the double beat theory and can this explain Beethovens metronome markings? It is a theory I was introduced to by Wim Winters and his youtube channel «authenticsound», so if you want to know more about the theory you can visit his channel. The double beat theory is the only theory I have come across that is based only on sources and evidences, but I think Wim believes in this theory so much that he ignores the evidences that go against it instead of trying to explain them. He also has a reputation of simply ignoring or blocking people who doesn't agree with him instead of having an open discussion, which sadly makes him loose a lot of credibility. So even though he talks a lot about this theory in his youtube channel, I wanted to take a look at it from a much more neutral and open-minded stand point, and see what evidences I could find to prove or disprove the theory. I think it is also very important to distinguish between evidence and personal preferences, so even though this theory might be correct I’m not saying we have to play like that.

The reason I’m saying that? The double beat theory indicates that all of Beethovens metronome markings should be halfed. I’m going so explain why, and show the evidences that support this, but the basic principle is that all of Beethovens metronome markings should be halfed. You might think the music would be really boring and slow, but it would at least explain why the markings are so high. And as I said earlier, even if the evidence shows us they halfed the metronome numbers back in Beethovens time doesn't mean we have to do the same today. The whole meaning of this project is to open up our possibilities as performers and not limit ourselves to any theory, and I think the double beat could open up the possibility of sometimes taking the tempo down, not necessarily half tempo, and have time for all the details that sometimes get lost when we play as fast as we do today.

The text above is an excerpt from an article published in London, 1816, in The Times and Morning Chronicle, called «Directions for using Mälzels Metronome». Note the last sentence which is the basis of the double beat theory: «each SINGLE tick forms a part of the intended time, and is to be counted as such; but not the two beats produced by the motion from one side to the other.»

So what does this mean? That they only counted the metronome one way, and not both ways as we do today, meaning if we use the metronome how we do today we need to halfen the numbers. So the double beat theory says that Beethovens metronome worked fine and the markings was meant to be followed, it is just that they used the metronome in a different way than we do today, which I would say is a much more plausible explanation than any other theories. When I initially heard about this I thought it sounded weird and the music would be boring and too slow, probably what you are thinking now, but as I stated earlier we need to eliminate our personal preferences and just look at the facts for now. But why would they make it so complicated? For example if Beethoven gives us ‘quarter note = 100’, it means the metronome would tick in 100 like it does today, but the quarter note would be only the one way, so it would actually be in 50. Sounds a bit too complicated and weird, right? Well, let’s say you were to show someone how fast you want a piece of music, and you beat the tempo with your hand on a table. You would only count the beats when you hit the table, not your hand on the way up, and so if you translate that motion to the metronome the natural way would be the double beat, counting it only one way and not the way back.

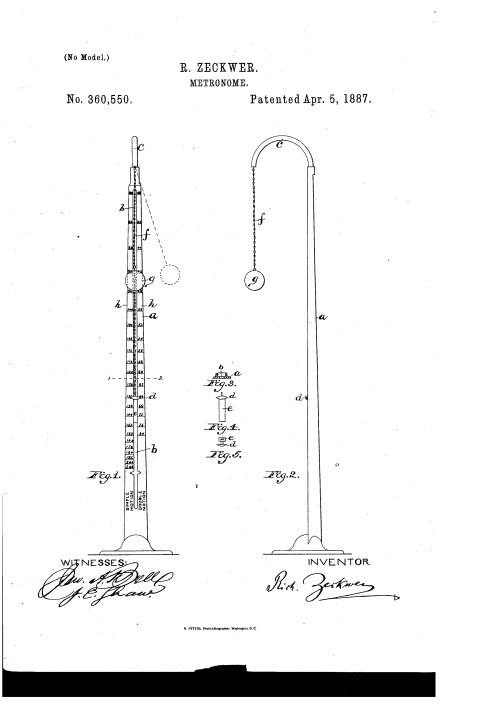

This is a patent for a version of the pendulum metronome, made by Robert Zeckwer in 1887, but the pendulum metronome dates back long before Beethovens time. It is basically a string with a weight at the end of it, and depending on the length of the string and the heaviness of the weight, you could get different tempis. What is really interesting about this patent is that it shows another reason why they might have used double beat, but also a turning point to when they might have started using the metronome how we do to day, often referred to as single beat. In this patent Zeckwer explains what he calls a double scale, so for example on 80,40, it depends if you are counting both directions as one (double beat - 40), or each direction (single beat - 80). This practise dates back to long before the invention of Mälzers metronome, when they only had the very primitive pendulum metronomes, and the reason they did this was because if you wanted a slow tempo you would need a really long string, so instead they just counted half the beats (double beat), and I think this practice together with the physical beat, as explained with the hand beating on the table, might be the reason they used the double beat when Mälzers metronome was invented.

This is one of four metronomes I found in Vienna, all with the exact same scales, and this one is dated around the 1830s. At first glance I thought they were really fast, for example an Adagio is set to be 100-120! Compared to todays adagio which is around 60-70 its almost doubled, so did they just play really fast back then, or maybe they used the double beat? If you look at the scale of the metronome above and half all the numbers, they would make a lot more sense, and I wouldn't say it's just a weird metronome since I found four different metronomes in different museums, dating from the 1820s to the 1860s. Sadly most museums don't allow pictures which is why I only have this one, but I thought these scales were really interesting, and to see how we as performers can use it. For example when playing one of Beethovens cello sonatas which doesn't have any metronome markings, I tried to follow the scale of this metronome, so for example the allegro had to be between 150-180, and I can honestly say it was so fast it was just silly! When applying the double beat it was no problem, but then it was too slow for my taste. So for any musicians reading this, you can try yourself and apply this scale to a piece you're playing, and see what you think is more likely to be the solution, single or double beat?

So now that we know what the double beat theory is, I will discuss it in the next article and show you some more evidences supporting it, but also some evidences that might disprove it, so stay tuned and subscribe to get an email when the next article is published!

And as always, feel free to leave a comment if you want to share your thoughts or if you have any questions.

Thank you for reading, Markus Eriksen