Interpreting Beethoven: Single vs Double Beat

Hello and welcome to my last metronome-related article. I have to admit I didn’t expect it to be so much focus on the tempi, but as we have discovered in the previous articles it was extremely important for Beethoven, and I think it is very interesting that after so many years of research we still can’t say for sure what was the Tempi Beethoven wanted, even with the metronome numbers! In the last article I explained the Double Beat Theory and a few sources suggesting this might be the most probable explanation to Beethovens high numbers, but in this article I am going to explain and show you some more evidences that both proves and disproves this theory. I am going to show you why we can’t say for sure what is right or wrong, because there are a lot of evidences for both Single and Double Beat.

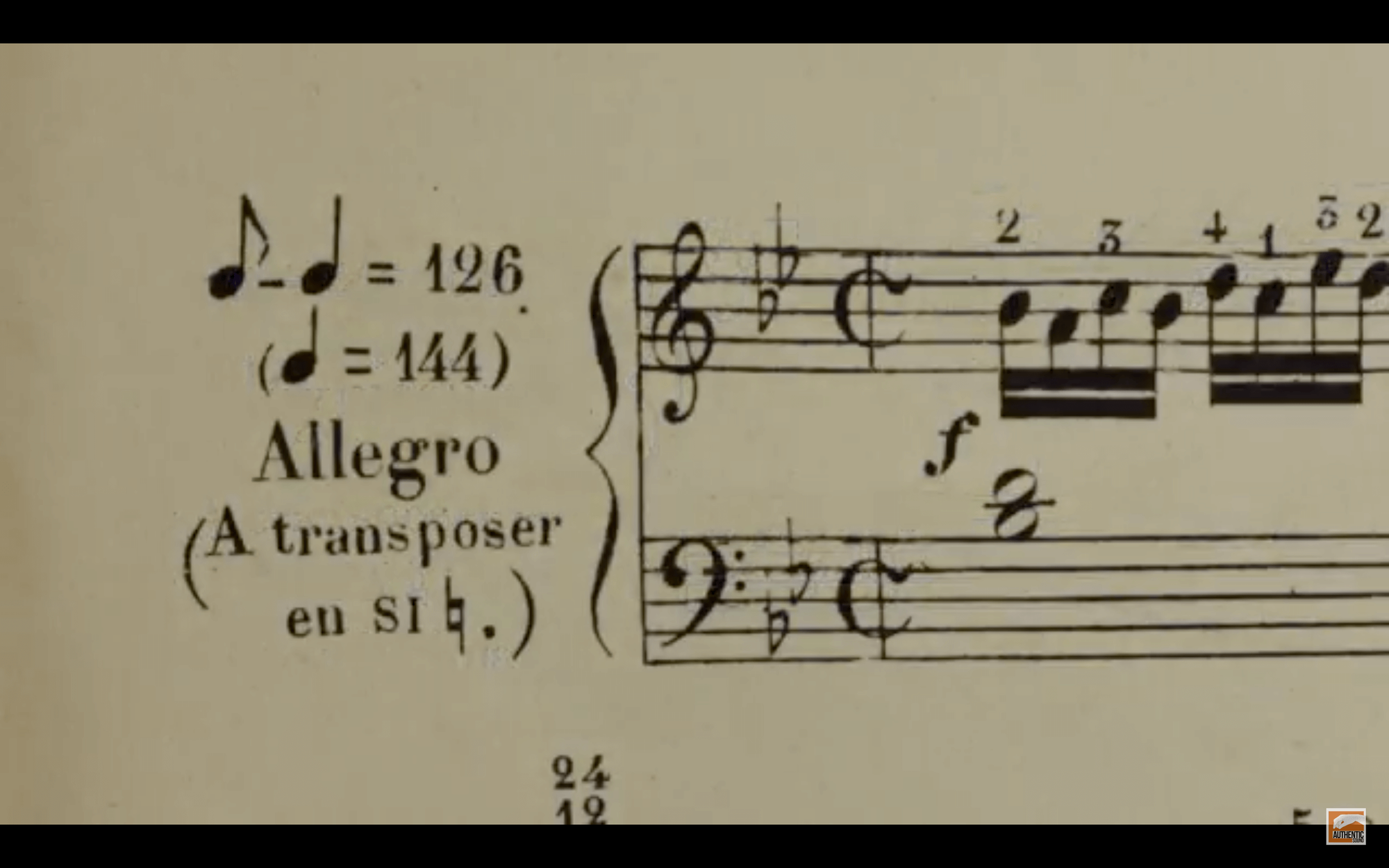

On the pictures above (borrowed from Wim Winters/Authenticsound) you can see some excerpts from the Clementi etudes edited by Isodore Philipp, and as we saw in the last article with Zeckwers double scale, the metronome numbers here might indicate the transition from Double to Single beat. Some of you might think this is just to show you how to practise, start with the quarter note on 69 and work your way up to half note on 69. But that would be a weird way to indicate practise speeds, and the more natural way would be to write for example half note = 40-69. Another reason why I think this is an indication of Double/Single Beat and not practise speeds, is the preface to the etudes. «To Arrive at the indicated time, one must practise by preference, slow and loud.»

So why would Philipp, who wrote this preface, give us an exact metronome number for practising, when he tells us to practise slowly by preference? And if you look at the picture to the left, he even added his own metronome mark to be even faster than Clementi. In this example Clementi put in the metronome marking 1/4 = 126, and Philipp added the 1/8 note as well as his own preferred speed (144). With this and the preface in the back of our heads, I believe the most logical explanation would be to say that this is an indication of the transition from Double to Single beat. I would also like to mention that in one of the Clementi etudes, the metronome marking if read as Single beat, would mean you have to play a speed of 1200 notes per minute. A quick google search says the current world record in piano playing is about 800, so either Clementi and everyone who played his etudes at that time were a lot better than todays pianists, or maybe the Double Beat theory could be right?

Charles Marie Widor

For the next example indicating the Double Beat Theory, I would like to introduce the French musician Charles Marie Widor. He was a highly respected organist, composer, teacher and musicologist in the late 1800s, and is mostly known today for his ten organ symphonies. He is a interesting man to read about, but I am especially fascinated with what he said in an interview in 1899

«A few years ago I heard a Haydn Symphony conducted by an old man, who claimed to hold on to the real tradition of Haydn, as taught to him by his father. His tempi was about half of ours.»

It would be easy to say this conductor was just a crazy old man and shouldn’t be taken seriously, but when it comes from the highly respected Widor and he goes on to explain why he thinks musicians are playing so much faster, he obviously agree with this man. After all, this old conductors father would have been active around the same time as Haydn, so I think we should take this seriously and recognise that we have a source dating back to a musician working at the same time as Haydn, claiming we had doubled the tempi already in the late 1800s.

John MacDonald: « A treatise explanatory of the violoncello»

(London, 1811)

This is a cello school book I would like to mention, since it gives us valuable insight of what a professional cellist in the same period as Beethoven and Haydn, thought about music and tempo. This book was made on commission by George, the Prince of Wales, which gives it some credibility and would indicate that John MacDonald was a highly respected musician since he was chosen by the prince to write this. If you read my other articles you would know the metronome was invented five years after this book was published, so what is interesting about this book when talking about Double Beat Theory?

Well, they had something known as the pendulum metronome for many years before the invention of the modern metronome. This was basically just a string with a weight on the end, and depending on the length of the string, how heavy the weight was, and how high you lifted it, you could use it to get different tempi. In this book MacDonald explains the meaning of Adagio, Allegro etc, and he also explains how to get these tempi with the pendulum metronome. He explains the length and weight and how you could find the exact tempi with your pendulum metronome, and how many beats per minute this should give. I tried it myself and can say it was quite accurate, but the interesting thing is how fast he claims these terms should be.

According to MacDonald, Adagio should be 64 on the eight note, and Largo 80 on the eight note. To avoid the need of too long ropes, you counted these as both directions as one (double beat), and to make it easy MacDonald claimed Allegro was exactly twice as fast as Adagio, 64 on the quarter note, and here you could just count it one way (single beat). The same is with Alla Breve, which should be 80 on the quarter note, and you could use the same rope as for Largo but count it one way instead of both ways.

Carl Czerny: Pianoforte-Schule op. 500 (1839)

Wim Winters from Authenticsound often talks about Czerny to be a very important source, and even talks about this piano school in particular, but here are a few examples I don’t think Winters wants you to know about. This is one of the reasons I don’t think he can be trusted and looses a lot of credibility in my mind, since he obviously knows about the examples I’m going to show you, but since they don’t fit into his theory he never talks about them.

So why is Czerny such an important source when talking about Beethoven? He was the student and friend of Beethoven, and in the later years he would step in for Beethoven when he was unable to play himself. Czerny knew how important the metronome was for Beethoven, so after his death he often edited pieces and added metronome numbers according to how fast Beethoven played them. In his op. 500 piano school he even had an entire section on how to play Beethoven, which I would highly recommend to any musician interested in playing Beethoven.

«Beethoven himself was unsurpassable in legato playing to the great astonishment, as those of Liszt, Thalberg and others present.»

One interesting thing I realised when studying this, is that Czerny never talks about how fast Beethoven played, and he never mentions that these are high metronome numbers or that any pianist struggled with the tempi. I find this very interesting, since Czerny talks a lot about how expressive Beethoven played, how extremely loud/soft he played and his great legato playing, but never about the speed. Something interesting to keep in the back of our heads when we take a look at a few examples that might disprove the Double Beat Theory.

«(…) For Example M.M.♩= 112, we must play every quarter note exactly with the audible beats of the metronome.»

This quote alone could disprove the entire double beat theory, note how Czerny explains that every quarter note should be played with each AUDIBLE beat of the metronome, not every two audible beats like the Double Beat Theory suggests. This next example is from Czernys explanation of a walz in 3/4, the biggest problem of the Double Beat Theory. Why? Because if you play a 3/4 bar with the Double Beat, you end up with playing three against two, something I struggle to believe they did back in the 1800s when just practising a simple walz. It all seems a bit too complicated, and you would expect Czerny to mention this in his piano school book when explaining a walz, right?

«(…) a dotted halfnote = 88; consequently a whole bar lasts only during one beat of the metronome and is the true time of the walz.»

Sadly he doesn’t even mention anything about that, which is a big problem for the believers of the Double Beat Theory, but if you are a Double Beater and have an explanation to this I would love to hear from you!

Conclusion

I hope you have enjoyed reading these articles about my tempo research and Beethovens metronome markings, and hopefully it helps us to be more conscious about the tempo when playing this style of music. There are a lot of theories about why Beethovens markings are so fast, but as I have tried to show you it is impossible to come up with a true explanation without ignoring some of the evidence. I would have loved to be able to tell you that I finally found the solution and why everyone else is wrong, but sadly I can’t do that without ignoring some evidence, and it is much more important for me to show you everything and get the discussion going and help bring awareness to musicians about our choices of tempo.

In the next article I am going to discuss Beethovens extremely long bowings and how us string players can tackle this, so stay tuned for that. Please feel free to leave a comment if you have any questions or remarks, and subscribe to get an email when the next article is published.

Thank You for reading,

Markus Eriksen